frame 20 January 2022

In Conversation:

Jason Pierce with Lenny Kaye

Jason Pierce is the frontman and sole permanent member of the British band Spiritualized. He previously co-fronted the alternative rock band Spaceman 3. He has collaborated with many musicians including Dr John, Primal Scream and Yoko Ono. In 2005, he played with Patti Smith at the Queen Elizabeth Hall for her tribute to William Burroughs.

Musician, writer, and record producer, Lenny Kaye has been a member of the Patti Smith Group since its inception in 1974. His seminal album-anthology of sixties' garage-rock, NUGGETS, is widely regarded as defining the genre. His new book, LIGHTNING STRIKING, is a personal take on the history of rock and roll’s most influential movements and moments.

We thought it would be fascinating to get these two acclaimed musicians together, to discuss aspects of LIGHTNING STRIKING and their own lives in music.

Jason Pierce and Lenny Kaye © Ulf Holberg

Jason Pierce: Did you ever feel like, ‘How the fuck did I arrive here’?

Lenny Kaye: Oh, all the time. Especially for one as untrained as I am as a musician. I always loved rock and roll - played in bands as a kid. But to still be doing what we do 50 years later – and for something as off the beaten path as Patti…? She and I never thought we would have a rock and roll band when we started, in fact we didn’t know what we were doing, we just had something that created a fascination in those who came to see us, even though they didn’t quite know why… And us - we’re figuring it out too. How to take these poetics, and rudimentary rhythms, and make it… something, you know, whatever that something is. And we never tried to steer it. I think that’s really the success of whatever it is we’ve done, since our first reading in Feb of 1971, a half century ago.

JP: Wow, was it that early?

LK: Yeah. And then we didn’t do anything for another two and a half years. It was not really meant to be a band. Even when we restarted, playing once a month at these poetry events we did, we didn’t really have a direction. But by the time we added JD as our drummer in ‘75, we had a band that sounded like us. And that really is important.

And of course, Patti is one of the world’s great, great charismatic performers, totally in the moment. I like to say that I’ve stood stage left with her for all these years and I’ve never, ever seen her sing a false note or go on cruise control. She engages with the audience, she has something to say, and she wants to say it. And she wants to empower and illuminate our shows. We all want to get to the same place, which is this kind of ecstasy. She’s just very powerful and all I try to do is get to the door and open it before she hurtles through, and it’s a great thing.

We’ve been together a long time. We just played in Amsterdam – Patti singing and me playing acoustic guitar. And she’s every bit as there as when we have the full band. So it’s a great thing to watch, and to grow old with it. It’s been a long haul. Several tangents and roundabouts but we’re still here. I would’ve learned to read music if I’d known I’d still be playing it a half century later!

Patti Smith and Lenny Kaye performing together. Charlie Steiner – Highway 67/Getty Images

JP: But do you think you would have? Because you talk in the book about that kind of rock and roll essential spirit - almost - you don’t say ineptitude, but I think rock and roll should be kind of inept and slightly stupid –

LK: I like overreaching though, especially when the overreach doesn’t quite make it, so you topple into a whole new area. I think music can seem very simplistic, but it’s often deceptive. I mean, The Ramones are always held up as a simplistic band, and yet, if you play ‘Beat on the Brat’ or ‘Rockaway Beach’, there are so many weird twists and turns. It’s a skill to be able to make the complex look simple!

JP: I like that you say something in the book - you add an ‘and roll’, like rock… and roll. And I’m fascinated with the idea of ‘rock and roll’ and I don’t really know what it is. Do you have an idea of what makes something rock and roll, and not rock?

LK: I think of the words rock and roll as almost like taking on a married name. Roll softens rock and gives it a swing. And it’s very descriptive of the music. For a long time, in rock’s glorious adolescence in the 60s, I knew a disc jockey who used the word rock-and-roll on the air of a progressive rock station, and they called him on it: ‘it’s only ROCK played here!’ But I believe you need the rock and the roll. And to me, they must seem like mates, basically.

*

LK: One of the themes of the book is how amorphous scenes grow together, and slowly develop their components of style. They become more defined. And in my mind, definitions define limit, as Mayo of the Red Crayola once famously said.

Punk Rock, when it figured itself out, became kind of an accelerated speedway, but you knew what it was going to sound like. In the early years at CBGBs, each band had what would be known as a punk sensibility. But in the end, they’re all different ideas. Blondie’s so different to the Ramones, so different to the Talking Heads, so different to Television, so different to us, just to name the top shelf of what came out of there. Were we punk? Was Blondie punk? When it got to England, it got a very definitive musical style. You couldn’t really vary from it without getting a lot of critical approbation.

I like things pretty blurry. I’m always into the initial shock and surprise of something that I've never heard before, and that really has yet defined what it is. It’s like a band – with their first album they’re figuring themselves out, by the third album they’ve defined themselves. So I would look to the second album, where they’re just like ‘what the hell are we doing?!’

CBGB in 1983 (Image credit: Jack Vartoogian / Getty Images)

JP: You can almost hear bands finding their ideas between their first and second - you can almost hear them learning as they go, and quite often when they get to 3 and 4 they’re kind of just playing through the motions… They’ve learnt the thing that they know how to do, and it’s harder to find a way out. But I like what you say about rock and roll. Because maybe I got too obsessed, or do get too obsessed with trying to say ‘this is rock and roll’ or ‘this isn’t’. I found myself in the Norwegian bit of your book, thinking ‘this isn’t rock and roll’ and where they’re quite literally burning down the churches and killing each other, it still wasn’t rock and roll enough for me.

LK: We contain multitudes, and you’re dealing with 50 years of styles mutating. And when you get towards the end of the book, the black metal, it’s like burning down the house, it's like starting again. And it’s interesting to see how these things interplay as rock and roll gets on. Just because it needs to keep renewing itself, it seems to get more crazy. But maybe it’s always been crazy. I just like this sense of evolution that I found looking into these ten music scenes. But, looking back, it’s like the Jurassic age, and the Pleistocene - you can see that things are happening on an evolutionary scale. Maybe we’re living in the Black Metal times now where we’re burning down the Church of Earth. And you know, what’s going to come next…?

*

JP: When I was reading the first chapter, initially I was thinking ‘oh no, not the Elvis story again’, but it was delivered really beautifully, almost like there was an ADT or slap-back echo on the script and it really put me there And also, I agree with what you say about the internet. It was the first time I’ve read a book where everything was available to be heard at the same time.

I’d never heard the Beatles Demos. I’d always heard the story that the guy who turned them down was a fool to have turned them down. When listening to that story, you understand it in hindsight, having heard ‘Rubber Soul’ and ‘Come Together’ and ‘Get Back’ and all those kinds of things. But the actual demos themselves are quite… pedestrian seems the wrong word to describe the Beatles, but they’re not stunning. They’re not as extraordinary as the Jerry Lee Lewis thing that you turned me onto – where he sings the Lefty Frizzell song, ‘Pease Don’t Stay Away So Long.’ I mean, he’s a child but you can hear Jerry Lee Lewis inside that voice! It was amazing to be able to play through.

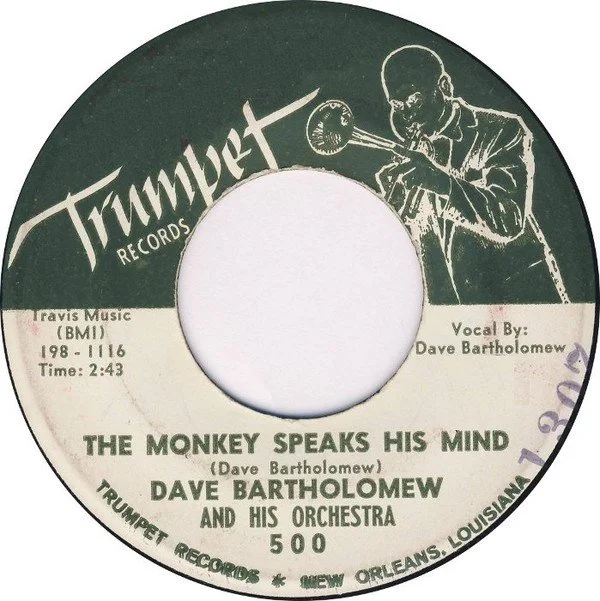

I thought your connections to New Orleans and Ska were really strange, because it’s not just a kind of fiction or an idea. You can play those records, ‘Stack-A- Lee” Mind’ by Archibald for example, or ‘The Monkey Speaks His Mind’ by David Bartholomew – and many others from that time and place and they are literally Ska music!

LK: Now everything is so easily available - I think it’s probably great because you’re going to get some really wild-card blending of stuff. But I like the fact that sometimes music develops without being able to be accessed. Like the San Francisco bands when I was a kid, they were just hearsay to me. I thought ‘I’m an aspiring hippie but I’m too young to go to San Francisco’. So, I just had my Fillmore poster on the wall. I’d never heard the Quicksilver Messenger Service, I’d never heard the Grateful Dead, I’d heard one Jefferson Airplane record, and it’s so early that they’re still kind of a folk-rock band. I would have wanted to hear the other bands but couldn’t. But this scene in San Francisco, for that year and a half at least, was kind of insular. The bands were interacting with each other, and the music was taking on its own personality.

I think the same thing is true for the CBGBs bands, because when everybody started playing there, say in 1974, you know, there might be 25 people in the audience, most of whom were in the other bands. I mean, everybody hoped, of course, to ‘make it’ - but really the opportunities presented in this bar in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by flophouses and people lying on the street, was that the music had a lot of time to develop.

With Patti, we played there, with Television, in the spring of ‘75, for like seven weeks. Every night we were just able to go there and play and begin to understand what it was we were doing. And at the end of the seven weeks, we had a better idea. Not that we knew where it was going or that we were going to be learning again over the next few years.

But I like when things are clustered. I love that phrase of Brian Eno’s - ‘scenious’ - it’s not just the bands, it’s the people there, it’s the mood, it’s the culture, it’s an ecology of ideas that over a course of time, harden into… harden into... something. Whatever that thing is. And after that, it becomes kind of known and figured out and easily transmissible. And after it really gets figured out, and becomes a cliche or a stereotype, then it’s time for something new.

*

JP: Have you read Perfecting Sound Forever by Greg Milner? That talks a lot about cylinders and how, when they first invented the phonograph, they would have concerts with the 78 playing, and the female voice singing simultaneously. The promoters would go ‘this is the band, and this is the gramophone!” And they’d switch between the two. The audience couldn’t tell the difference between the real voice and the recording. But, in fact, the singer was having to adjust her voice to capture the exact tone of the cylinder, rather than the reverse. It was a fakery right from the start!

LK: Records are fake, records are an illusion. I remember the group James, who I did a record with in the 80s. When they first called me up, they said they wanted to play live in the studio and choose the best track. I said ‘well, not exactly sure why you need me there - you know what you sound like!’ I believe that playing live in the studio is not the same as playing live to a throng of people giving you energy, when you’re playing at 120 decibels an hour in a sweaty club. You put that in a studio, you can play live as long as you want, but it’s not live. A record is an illusion of being live.

Lenny Kaye performing with Patti Smith c1976. Photograph: Gus Stewart/Getty Images

Sometimes it’d be nice to cut a record and leave three hours later having done it. As a writer I can write a sentence, sit back, smoke a joint, think ‘oh, I could use a better word there, maybe this sentence should go here’, and you know, move it around, ad infinitum. But you can do that in the studio now. Pro tools - it’s a whole different way of working. I remember in the early 90s, I had to splice a piano part together. So, the engineer says ‘just come back in three hours’. Whereas now… ‘you want it backwards?’ ‘You want it this way?’ You lose stuff, you gain stuff.

There’s a lot of discussion about digital vs analogue. I always make the joke, ‘Well, to me, ever since the cylinder, it’s been downhill’ But then I found out that’s it’s true. Because, on a flat disk, when you get closer to the inner groove, the fidelity goes. But a cylinder has the same thing all the way through.

JP: There’s a Rudy Van Gelder thing where he says if you don’t like the sound in digital, blame the engineer, blame the mastering house but don’t blame the medium. There’s nothing wrong with the medium, it’s is just a way of storing information.

LK: Oh yeah. It’s a funny thing, when the band is out there playing, everything sounds like crap, and everyone’s pissed off at each other – until, all of a sudden the band hits that moment - the sound magically gets better. I love great engineers, and I want my guitar to sound as beautiful as I imagine it, (because it doesn’t often sound like that coming out of the amp!) But really, if the passion is there, that’s what you need – like these old Delta Blues records. They were just recorded in a studio, the guy there just banging away, but you can feel the passion.

JP: That’s something that cuts through the noise as well. And in fact, when they take the noise off those records, they lose some of their beauty, in a way.

*

LK: It’s interesting when these moments in time happen and render everything before that obsolete. I’m sure when Elvis ascended, there was a whole generation of singers and players and style of music which suddenly seemed yesterday’s news. I mean, even Les Paul was washed away in the flood. Vic Damone, Patti Page with ‘How much is that Doggy in the Window’ – a whole style of music was suddenly rendered obsolete. In the same way that when Grunge came in - all of a sudden the LA Metal Bands were yesterday’s news. Every once in a while, there’s an upheaval like that.

I try to catch that moment when things change. Nothing happens just in these cities, obviously there’s a world mood going on. But these sea changes, when suddenly things get switched, I really find fascinating. At this point we’re standing a little bit outside the lifeline of rock and roll. In the book, I could actually step back and view the continuum of what the music was, and will always be. It’s a great music, and endlessly fascinating once you get deeply within it. I still find records and artists that I've never heard of before.

I spent a long time this week in the catalogue of Arctic Records, which was a soul label out of Philadelphia. And yeah, great stuff. I’d never heard of any of it. The Volcanoes. Who are the Volcanoes?!

JP: For every genre of music, you can keep finding new records. You can find a lot of Gospel Music records, because gospel was in every Church in America, and every church had someone making a 7-inch recording of whatever was being played and sung. These recordings were sold to the local people, or to the congregation. And they turn up all the time. And Northern Soul in the UK, (which I guess is just called Soul in America)… There seems to just be endless amounts of little-known Northern Soul recordings to discover.

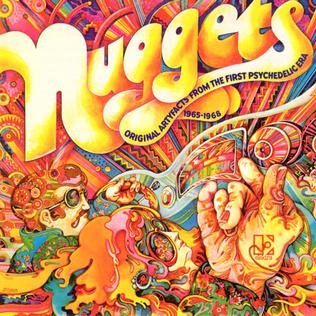

LK: The same with Nuggets. I said at the end of it that this is the start of an archeological dig, little did I realise how many garage records were out there. I kind of skimmed the top surface of recordings, many of which were really well-known in America. You know, I got the underside of the top-40. But I realised when the album got to England, no one had ever heard of the 13th Floor Elevators. So the revelation of this music was almost more astonishing.

I just had a new genre revealed to me couple of years ago. I bought this album called ‘Brown Acid - Songs from the American Comedown 1969-1972’, bands that sounded like Grand Funk Railroad, you know, little bit of Deep Purple and Black Sabbath, and there were some American bands like Dust and Sir Lord Baltimore. Kind of pre-metal heavy bands. I thought ‘Brown Acid’, now there’s a category for a little bin in the record store. It’s all out there. And again, we’re talking about a music that took over the second half of the 20th century. I know now, since 60,000 songs are uploaded a day to Spotify - there’s a lot of stuff out there. And there’s gonna be a lot of very, very strange genres happening now.

*

JP: Nuggets changed our lives. We were in small-town Rugby, introduced to the electric blues, and The Seeds, and The Elevators… in one double album, in one single package! It just changed our whole musical world.

LK: I never thought the record would come out, personally. It’s a miracle it did. So, I just kept asking for the moon – “I don’t like that cover’. I was so full of myself. But I don’t know, it really captured a moment in time. I take some credit for figuring it out but I was just going on instinct and the unconscious. I didn’t have the long view.I didn’t try to make it complete or anything - these songs all seemed to fit together. I was just lucky to be there first. And that Elektra was so open-minded. Just… ‘You want a double album? Okay. yeah sure’.

I’ve got to hand it to Jac Holzman, who really allowed it to happen. Same thing with Hilly Kristal who owned CBGB, I don’t think Rock and Roll was his favourite music. Hilly liked Country, Bluegrass and Blues. He liked a good fiddler’s convention. But when it happened, he allowed it to happen. He just said ‘You can play here, but you have to play original music.’ And the original music became the hallmark of CBGB, which is a remarkable achievement in the dog-eat-club world of night spots.

I went out last night actually, I was in Soho, and since I kinda like pre-Beatles British rock – you know, the Johnny Gentles and the Marty Wildes and the Vince Eagers, Adam Faith, I took a walk to where the Two i's club used to be on Old Compton Street. Took my picture in front of it, which was exciting, probably will be an Instagram post one of these days… but I just thought, ‘Here is where something happened’. In the same way that when we play the Fillmore I get to stand in the spot where John Cipollina stood. I like these holy sites.

JP: Have you played the Apollo?

LK: We have.

JP: There’s a weird thing on the way up to the stage, a handrail made from the tree that used to grow on the site, where it’s worn smooth, like a religious icon, people’s thumbs grabbing the rail…

LK: And of course tiny, tiny dressing rooms. You can just imagine ‘Sonny Til `and the Orioles in this one’, ‘Billy Ward and the Dominoes in this one’, ‘oh, here’s Clyde McPhatter’. It’s a great place. And you got to treasure these places, because they might not be there forever. I love playing the Paradiso in Amsterdam and there’s a place in Vienna called the Arena, which we’ve played many a time. And to play Royal Albert Hall, I mean, come on..! These are great places, but the kinds I really like are when I’m downtown in the East Village, and my buddy’s having some show in an upstairs bar, and there’s an extra guitar there, which I get to bang on and holler, and I don’t have to worry about the business of making music - I can just sing for pleasure. And doing so, every once in a while, you can enter into the present tense of that moment, which is so beautiful. Music exists in the present. I know I say that in the book, but it’s hard to overemphasize - when you’re playing, and somebody is listening, you’re in the moment. Normally, it’s very hard to be in the moment. Usually you’re thinking ‘I did this, or I didn’t do this, dabadoo, dabada’, but when you’re playing music, and you’re there, you’re concentrating. You’re in the moment in the same way as when you’re listening to music and it has a movement to it. A painting, yeah, you can stare at it but it’s not movement. There’s a certain kinetic movement to music, that when you’re listening to it you’re absorbed and following its lifeline. And because, in many ways, it’s not as literal as film, you’re dealing with musical tones, frequencies.

JP: In fact, the tone that you hear is exactly the same resonant frequency in your brain. So your brain resonates with it. It’s quite amazing that the connection is that literal. And I’d like to read your book again, but maybe I’ll only return to it once, twice, I don’t think I’ve read a book more than twice. But music - we return time and time again. Even when we know the information that we’re going to get, we come back again and again. And the human brain has got this odd way - it forgets so much stuff but it can almost remember, almost fully intact, the details of a song. It’s not just the hook, you can remember the bassline, the way the drums enter, the backing singers’ voices… Everything about it.

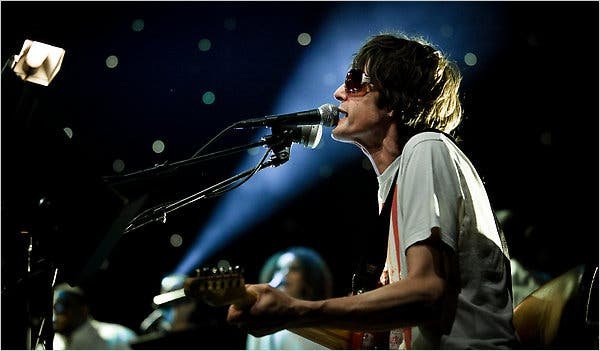

Jason Pierce performing with Spiritualized © Chad Batka for

The New York Times

LK: If I’m learning a new song nowadays, I usually have to have a cheat sheet, or go garble, garble, garble. But I’m amazed that when I listen to music from my youth. I remember the inflection, every word.

JP: Even the gaps between the tracks - I know exactly when the next one’s going to come in.

LK: It gets inside you. I don’t know how. I think it’s the most mysterious of forms. And it’s not even confined to Western music. I can hear music from Africa, or Japan where it translates. You can feel the emotion behind it even if you don’t know what the lyrics are, even if you aren’t really familiar with the scales and the chords and the style, you can hear the certain way that it touches you. I find that mystical and magical and very mysterious. I mean it amazes me that I can sit here so many years after I started as a young’un, buying records in my neighborhood shop, that I’ve been able to sustain a life of music. I probably would have done something within it, or it would’ve been my hobby or something. But the fact that I can sing it, and play it, and write about it, and go to that random record fair and come out with ‘look what I got!’ - it’s a great privilege. And I really feel like in my book, I was able to pay tribute to it. I didn’t really want to write a memoir. I’m not even that interested in myself, to be honest. But I did experience the music as a participant and as a fan, and as a player. And so, I wanted to kind of reflect that, but I didn't want the focus to be on me-me-me. I wanted it to be about the music. And how it seemed to me, however I was aligned with it in any time, as it went through its lifetime. Which, for luck or fortune or whatever, seems to mirror my lifetime.

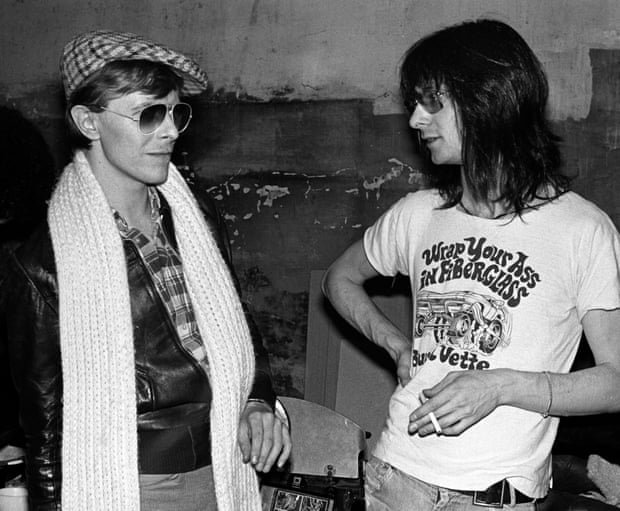

Kaye with David Bowie at CBGB, New York City, April 1975.

Photograph: Richard E Aaron/Redferns

JP: Your connection to that is what makes the book really special.

LK: Thanks. It’s strange to hold it now. I always like that part when you participate in the making of a record when you stop hearing it as ‘here’s the bass drum’ or ‘here’s the guitar part’. You stop hearing it as its parts, and all of a sudden, you’re listening to it as a record.

JP: And almost as if it’s somebody else’s record. When you make something and it starts to sound like somebody else’s record – it’s not that you’ve copied somebody else, it’s just that it seems to have come from somewhere outside of yourself.

LK: Or when you’re sitting in a random cafe and something you’ve worked on comes through and you think ‘oh, that sounds familiar’ and then you suddenly realise, ‘Hey!’ Music can take itself so seriously. It can be like business. I remember in the early 90s when I was producing, hardly playing. Really involved in bands, and tapes - ‘Mr Producer’. I go to CBGB’s one night and there’s this band on stage you know, really trying hard, but not for the people, for the A&R person they hope is out there. And I’m disgruntled. And then I get a call from the guy who’s now the bass player with Patti, Tony Shanahan. Tony’s from my home town in New Jersey, New Brunswick. He says ‘Hey, every Wednesday we have a kind of gathering at this local bar, the Melody Bar, we call ourselves the Slaves of New Brunswick, want to come down? We’ll have an amp for you. Just bring your guitar, sit in and have a good time.’ They’re playing and nobody cares who they are, or who I am. We’re just the band, like playing at the fraternity party. Kids are out there getting drunk, or picking each other up occasionally, hooting along with the band. And I realise that’s what it’s really about. It’s not about having a hit single, or doing this, or satisfying this. It’s just like the fun and enjoyment and real-time of playing. I still try to keep that in mind, wherever we play. Royal Albert Hall or anywhere. You’re feeling the music at that moment. And that’s a beautiful thing.

LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM - SEPTEMBER 5: Guitarist Lenny Kaye performs on stage with Patti Smith in the background, at Wembley Arena, on September 5th, 1979 in London, England. (Photo by Pete Still/Redferns)

I just feel lucky that I can access this. It’s not easy. You know, sometimes you feel the occasion too much or sometimes you feel the self-consciousness of what it is you do, which is essentially showing off and showing out. I just try to realise yeah, there’s a bunch of people out there, we’re gonna be there; we’re pickin’ each other up. It’s like that scene in the romcom about Seattle… Singles. Matt Dillon is a loveable lunk, and there’s a scene when Alice in Chains is onstage, and we’re thinking ‘we’ll have a lot of close ups of the band – but no. It’s mostly the band banging away onstage, and the focus is on Matt trying to put the make on whoever’s the gal he’s trying to pick up… and I thought yeah, that’s what it’s like. I spent as much time outside on the sidewalk of CBGB trying to sing harmony with Seymour Stein than going in. You know, I remember the night he discovered the Talking Heads. We’re out there trying to pretend we’re the Paragons or the Jesters or something, and he hears the opening notes of ‘Love Goes to a Building on Fire’ and he goes, ‘Oh, excuse me - sounds good’, and goes in there and signs them. But I spent as much time outside in the Bowery, you know, shooting the breeze, trying to think if that girl over there is gonna look my way, or maybe I need a beer, or whatever. That’s the casual part of these scenes. It’s not just the superstars.

JP: I like the thing you say that it’s also for entertainment. Jimi setting his guitar on fire at Monterey wasn’t a singular event. It wasn’t the first time he’d done that - it had happened many times leading up to that moment. Because, essentially, it’s entertainment. It looks great and it’s a fucking amazing way to end the show.

LK: You’re show folk!

JP: It’s show business.

LK: In the end, it’s just fun. I mean it’s a really serious business, and that’s what music is about. But in the end, it’s Spinal Tap: ‘have a good time… all the time!’ It’s kind of my credo too. My old aphorism used to be ‘Every night is New Year’s Eve’ from Delicious’ by Jim Backus: ‘we’re gonna have fuuUUUN!’ It’s one of those laughing records, you know, a guy and a girl are sitting round a table and they’re progressively getting drunker: ‘WAITER, I EVEN LIKE THE CORK!’. Anyway. You had to be there… And you can be! Jim Backus: Delicious. That’s my last recommendation for today.

Click here to read the unedited version of Kaye and Pierce’s conversation.

Lightning Striking is out now. Get your copy here.

Spiritualized's upcoming album Everything was Beautiful comes out 25th February. Pre-order the album here.