frame 67 May 2025

Getting in the Groove

by Gilson Lavis

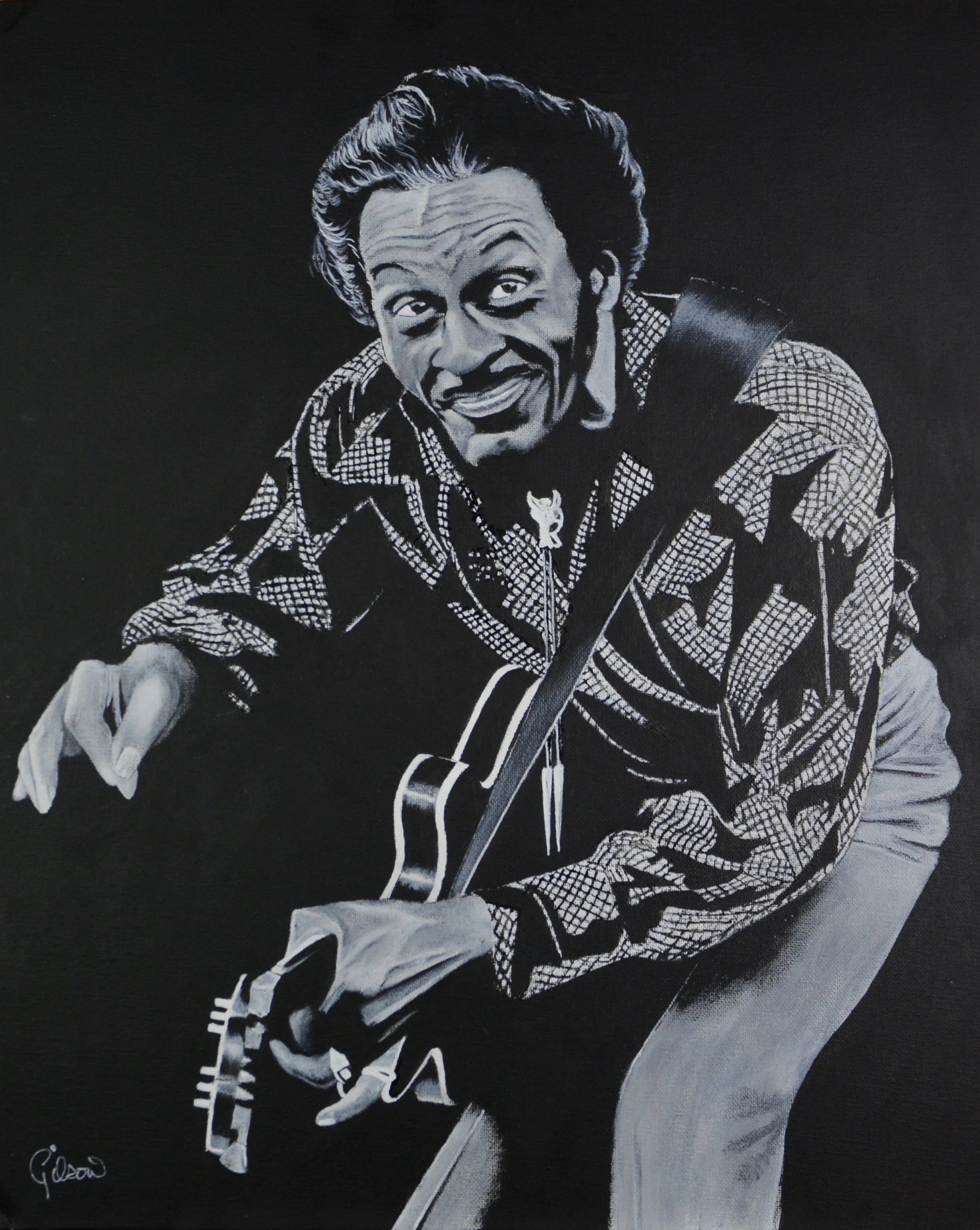

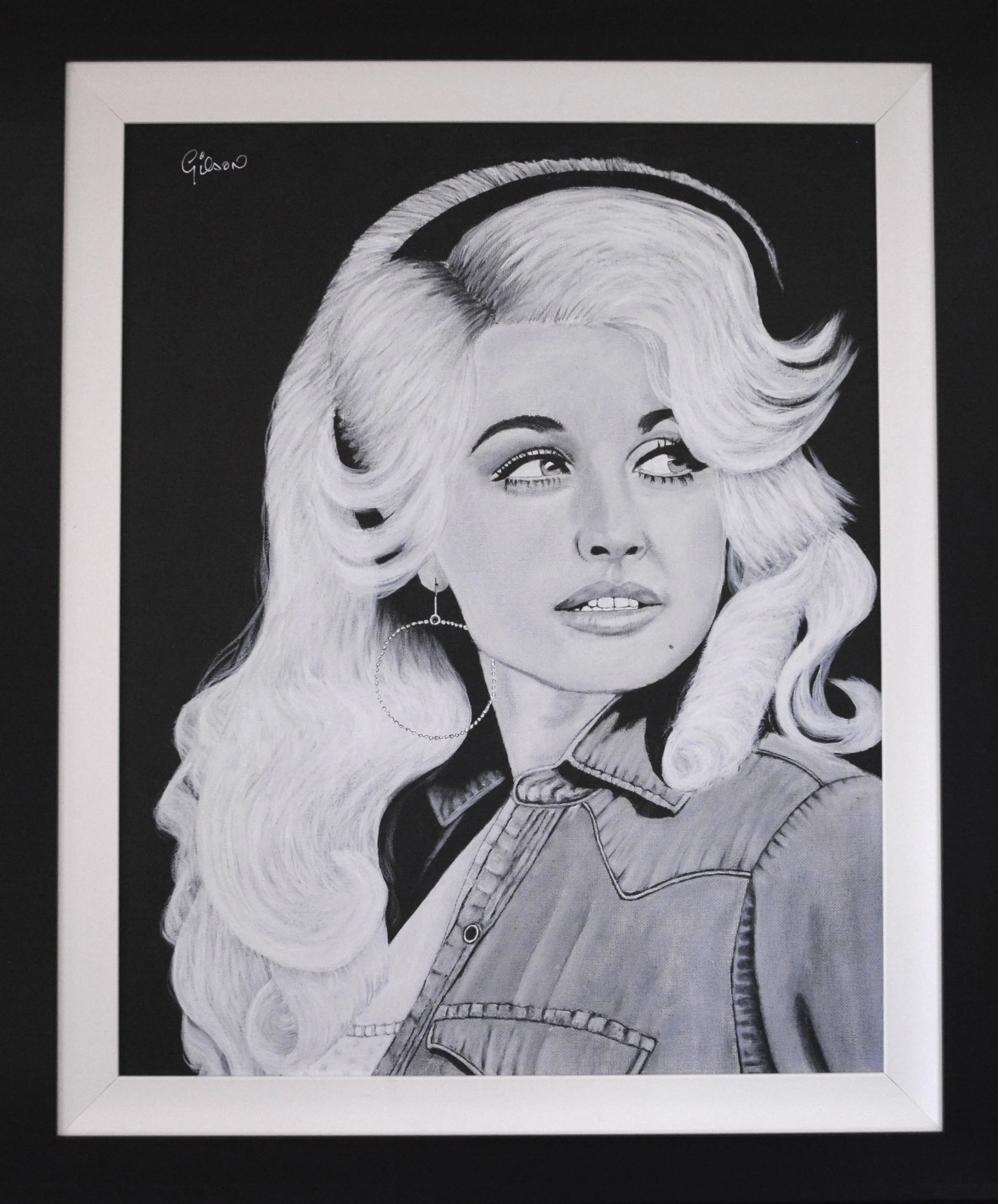

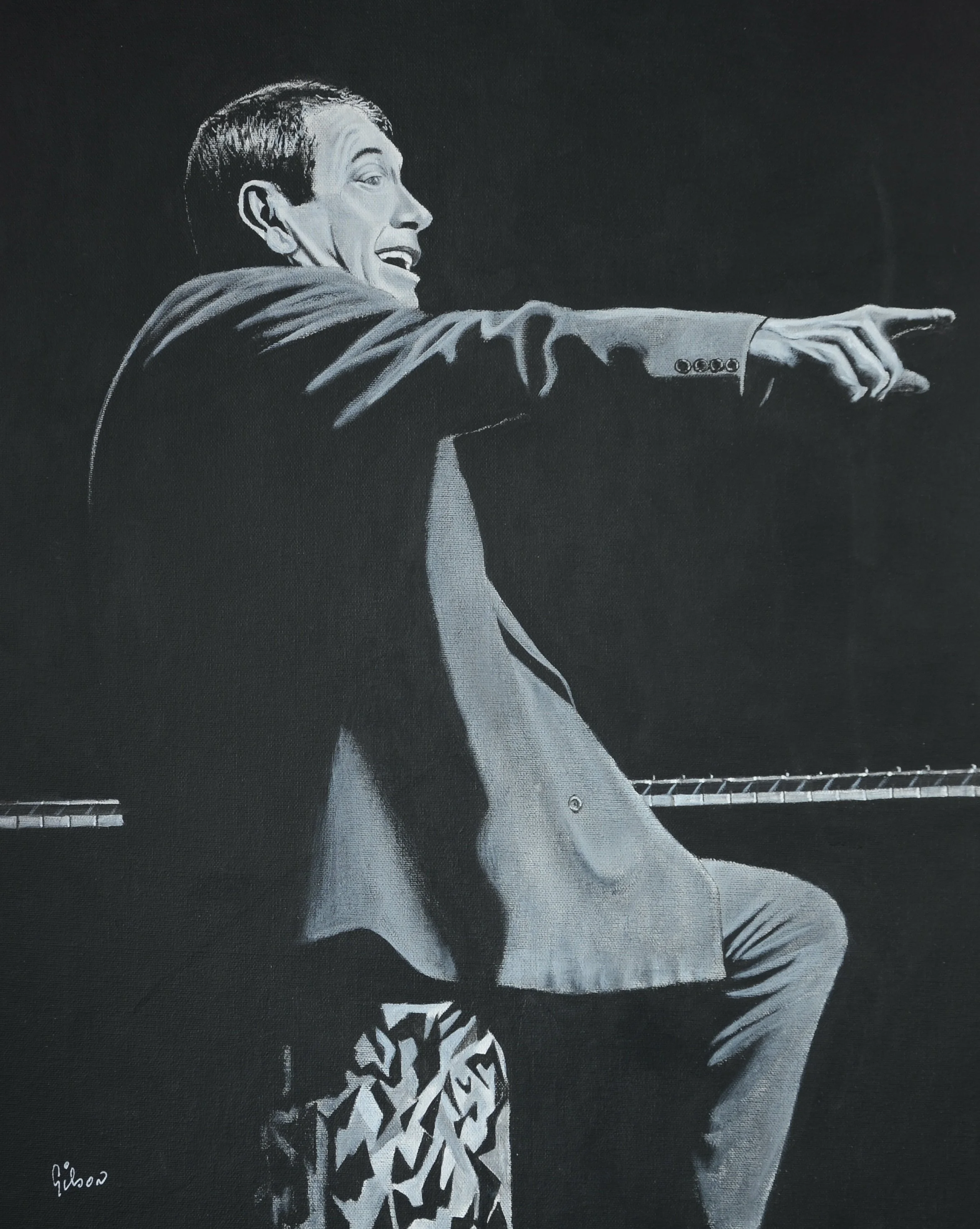

Gilson Lavis has been a legendary drummer for over sixty years. In his early career he toured with many well-known artists including Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis and Dolly Parton.

He was then the drummer for Squeeze and, later, Jools Holland’s Rhythm and Blues Orchestra. He retired from drumming in 2024.

Alongside his work as a drummer, Gilson has been a prolific and acclaimed portrait artist, depicting many of the musicians he’s worked with throughout his career and exhibited worldwide.

His most recent exhibition was held at the Salomon Arts Gallery in New York

Getting in the Groove

I became a drummer by mistake. Back in the early ‘60s, when Beat music was the apex of cool, the quickest and most effective way to climb the slippery ladder of social standing, and, more importantly, to impress the ladies, was to play in a group. But the Beat group at my school had about seventeen guitarists and no drummer. The solution was obvious: I would be the drummer. There were only a few, very minor obstacles in my way: I didn’t have a drum kit, and even if I did, I wouldn’t know how to play it.

My determination to join the school band, by whatever means necessary, says a lot about the kind of kid I was. Co-dependency was my first addiction. If there was anything I could do to be more liked by my schoolmates, even by a fraction, I would do it. So, I took an old tambourine with the jingles ripped out, a pair of my mum’s knitting needles, and went to audition. If it can be called an audition. With my tongue dangling out I blitzed through a barely recognisable rendition of ‘Wipe Out’ by the Surfaris, the latest hit from one of the in-trend Surf bands. Begrudgingly, they agreed to have me. I don’t think they had much choice.

I then begged my parents to buy me a drum kit, and on my next birthday, to my disbelief, they presented me with a Beverly bass drum and snare, in red pearl, and a ride cymbal. For what must have seemed an eternity to my poor parents, Fred and Doris, and twin younger sisters Olivia and Carol, my bedroom at 233 Leagrave High Street, Luton, was a cacophony of clonks and clashes as I learnt my way around my new toy, playing along to tracks like ‘The Rise and Fall of Flingel Bunt’ by the Shadows.

There is nothing worse than the sound of a drummer who can’t play, and at the beginning I really couldn’t. The racket that shook the whole house cost us several neighbours in the process. Dad, bless his heart, had polystyrene tiles fixed on all the walls to try to dampen it, but it made no difference. Luckily I took to drumming like a sailor to rum.

It wasn't long before I’d teamed up with a local organist called Arthur Tuck and started gigging in the local pubs and clubs around Luton and Bedford, earning ten bob or a couple of quid. None of it would have been possible without my wonderful dad. He was our manager, roadie and driver rolled into one. I should have been more grateful, not just thinking about the money. But it was a revelation. It gave me the freedom to do what I wanted to do and become the person I wanted to become. I’d won my independence, I was half of a whole adult, I was the ripe old age of thirteen.

By the time I turned fifteen I was quite experienced and thought very highly of myself. The world of music was calling me by name, and I was following its call. In order to appease my school careers advisor, who didn’t consider drumming to be a suitable career path, I’d agreed to leave school and become an apprentice ladies’ hairdresser. But I knew it wouldn’t be for long.

During my brief stint as a hair sweeper in a Luton salon, I came across an ad for a rock group up in Glasgow who were looking for a drummer. The next day I hung up my apron and broom and jumped on a northbound train with nothing but some drumsticks and a bucketload of arrogance. Waiting for me at the other end, as I might have anticipated, was a gaggle of hairy-arsed, hard-nosed Glaswegian rockers. We played some tracks together and they offered me the job.

I headed back home and tried to convince my parents to let me go. It was brave of them to do so as they were caring people and had valid apprehensions about their teenage boy being so far from home. The reality of what was in store for me went beyond their initial concern, my bandmates being even more rough and rowdy than appearance would suggest. Highly proficient in beer-drinking and fight-starting, it was a challenge to keep pace with them. Trouble managed to strike wherever we went. Ducking from a swinging chair or flying bottle became a daily ritual.

During one of these habitual scraps I witnessed something that will be forever burned in my memory. Rage had got the better of one of the boys, and without thinking he took some darts from the board and fixed them into his fist before launching it at his opponent’s face. Thick, dark blood poured from the diagonal trail of gashes across the guy’s cheek as he tried to hold his face together with his hands. After six or so months of living and working with these firebrands the homesickness became overwhelming and I headed back to Luton.

In spite of the harsh realities exposed to me during my time in Glasgow – a lot for a young lad from Bedfordshire to take in – I was now thundering head-first down a road from which it was too late to double back. The music gods had claimed me for their own. So, after licking my emotional wounds, I got a little group of my own together and we headed out to West Germany. Rumours were flying around that the American army bases out there had a string of clubs and bars with house bands, so we thought we’d try our luck.

After a couple of successful tours, playing behind the likes of Edwin Starr, Arthur Conley, and Clyde McPhatter, we found ourselves in Frankfurt, washed up with no money and no means of getting home. The promoters we’d been using hadn’t paid us for the previous run of gigs, out of malice on their part or incompetence on ours, we never found out. Somehow we were able to land a job at the K-52 club, a seedy-looking place which catered to the American tastes: chicken-in-a-basket served on formica tables. Ladies of the night would linger in shadowy corners, waiting to get picked up by the drunk servicemen.

We slept in the dressing room, ate at the club, and worked for tips. We were one of two resident bands, and the two of us alternated, an hour on, an hour off, for all hours of the day except closing hours, which were between four and nine in the morning. I don’t think I saw daylight for the entire time I was there. It was like being in a cavern, an underworld.

Saving enough for everyone to get home was impossible, so we agreed to pool our measly earnings and draw straws to decide who would go first. Because it was my band, I volunteered to go last. During our travels we’d acquired some new members, and were now numbered at seven. We had our work cut out for us: tips for the band were always rare and usually small. Other means of getting money were required. One popular method was to take peoples’ money to the bar, buy them a round of drinks, and pocket the change. It was theft by any other name.

Somehow, we were able to gather enough cash to send the band home, one by one. But by the time it got down to me and the keys player, the owner of the club informed us we no longer met the basic criteria of a band, and we were kicked out. After managing to scrape together enough to send my final bandmate on his way, I was stranded, on my uppers and in need of a miracle.

My miracle came in the shape of a local girl I’d been seeing at the time. Her father had a minicab company and was willing to give me some work. With an A-to-Z of Frankfurt balanced on one knee and a German phrasebook on the other, I drove the cab, occasionally arriving in the right places, until eventually I had enough for the ferry across the channel.

I didn’t quite have the heart to break it to my Fräulein that I was heading home. I was worried she’d been harbouring fantasies of a lifetime eating schnitzel and wurst, with little grandchildren running around in their Lederhosen. So, out of sheer callousness, youthful gumption, or a combination of the two, I got into the minicab one morning, and without saying a word drove myself and my drum kit all the way to Calais docks. I left the keys in the cab, optimistically thinking they might work out what I’d done and retrieve it. But at that point I really wasn’t looking back. I put my drums onto the boat and set sail for the white cliffs of Dover.

I’d started writing songs a while before that. Almost always with other musos. It was a great way of making some extra cash – if it worked out – and if it didn’t it was a lot of fun. The British music industry was built on smaller artists and songwriters selling songs for bigger artists to perform. It still happens today but not at the same scale or in the same way. In those days anyone could turn up at a publisher’s or promoter’s office and try their luck by playing them a demo tape.

A mate of mine called Tony and I often used to head to Denmark Street, London’s ‘Tin Pan Alley’ as it was called, and try to sell the songs we’d written together. We couldn’t afford to make demo tapes, so Tony would play piano and I would sing, if you can believe it. I fancied myself as a bit of a crooner back then. One of the places we’d go to was Mervyn Conn Promotions. Mervyn was an unsavoury character, you could tell instantly that he was up to no good, and he later got found out for it. He didn’t buy any of our songs, but knowing we were working musicians he put us on his roster.

At that time there was a reciprocal arrangement between Britain and the States, where if an American artist came to the UK they were only allowed to bring a small number of backing musicians, and vice versa. Mervyn was one of the suppliers of British pick-up players. For a drummer like me, who could play a lot of different styles, there was plenty of work going. It was as a result of this scheme and through Mervyn Conn that I ended up playing with a number of big names like Jerry Lee Lewis, Dolly Parton, and Tammy Wynette, and eventually, getting the gig as the touring drummer for Chuck Berry.

Chuck was an odd character, perhaps different to his public image. Fiendish with women, a lot of which is now known about, he also loved nothing more than to play pranks on his bandmates and crew. Many times in airports he’d disappear, sending everyone berserk and panicked as they rushed around trying to find him, only for him to come out giggling from behind a pillar. That was one of the more benign of his many windups, which he seemed to take a sinister kind of pleasure in.

He was also incredibly stubborn and could have a monumental temper. You did not want to get on the wrong side of Chuck. I made life harder for myself when, a little while into playing with Chuck, I decided it was a good idea to start going out with his daughter, Ingrid. Aside from the obvious dangers, there were many perks that came with the relationship. Travelling between shows I would ride in the limo with Chuck and Ingrid while the rest of the band would be packed like sardines in a crummy old van. Being in such close proximity to Chuck never got easier, though. He was so unpredictable it was impossible to relax.

The shows were a different thing altogether. Playing behind him could be utterly electric, and when he was in the right mood and the band were in sync there was no better feeling. I never felt uncomfortable playing with him, but as with everything he did there was a level at which you couldn’t know what he would do next. If a crowd were rude to him, he had no problems walking out. It was Chuck’s world, and we were all just parts of the ever-changing scenery.

One area in which he was utterly predictable, though, was money. Touring seemed to be nothing more than an effective way of making cash for Chuck. Every gig had its price and everyone that hired him had to pay him in a very particular way. It written into all of Chuck’s contracts that he’d receive half of his fee before he left America and the other half would be handed to him in cash just before he went out on stage. He would then play the show with a thick wad of dollars – all payments had to be in American dollars – sticking out of his back pocket.

This method of getting paid did cause problems on several occasions, especially in Europe. There was one show in Lille where Chuck had been given francs instead of dollars, and he refused to go on. He stood at the side of the stage, tenacious as a horse, while the MC announced him to the crowd three or four times, each announcement followed by steadily diminishing cheers. I stood nervously next to Chuck, drumsticks at the ready, as this went on and on until eventually the promoter had to wake up a bank manager in town and beg him to open the bank, before returning some time later with the money exchanged.

It was a fall from grace when the pick-up gigs started to dry up and I found myself back in Luton a few months later working as a brick stacker. My dad had passed away while I was on tour, I had to sell my drum kit to make ends meet, and I’d turned to the booze. At this point I thought my drumming days were behind me. My hands had spent so much time holding bricks and pint glasses they’d begun to be fixed in that shape. I knew that if I’d ever play again I needed to do something about it. With what she had left from the insurance payments after Dad died, I convinced my mum to buy me a new kit.

Being the cocksure and self-interested piece of work I was, I got the most elaborate set of drums money could buy, the Ludwig Octaplus. It had eight tom-toms going around the drum kit on which I could do ridiculous fills. After teaching myself once again how to play, I responded to a tiny ad in the Melody Maker for a South London band called Squeeze who needed a drummer. I went down there in my mum’s car, showed them what I could do, and they took me on. And so began the next chapter in my life. None of us knew it at the time but we were about to go on quite the journey.

With thanks to Cy Worthington