FEATURES

May 2021

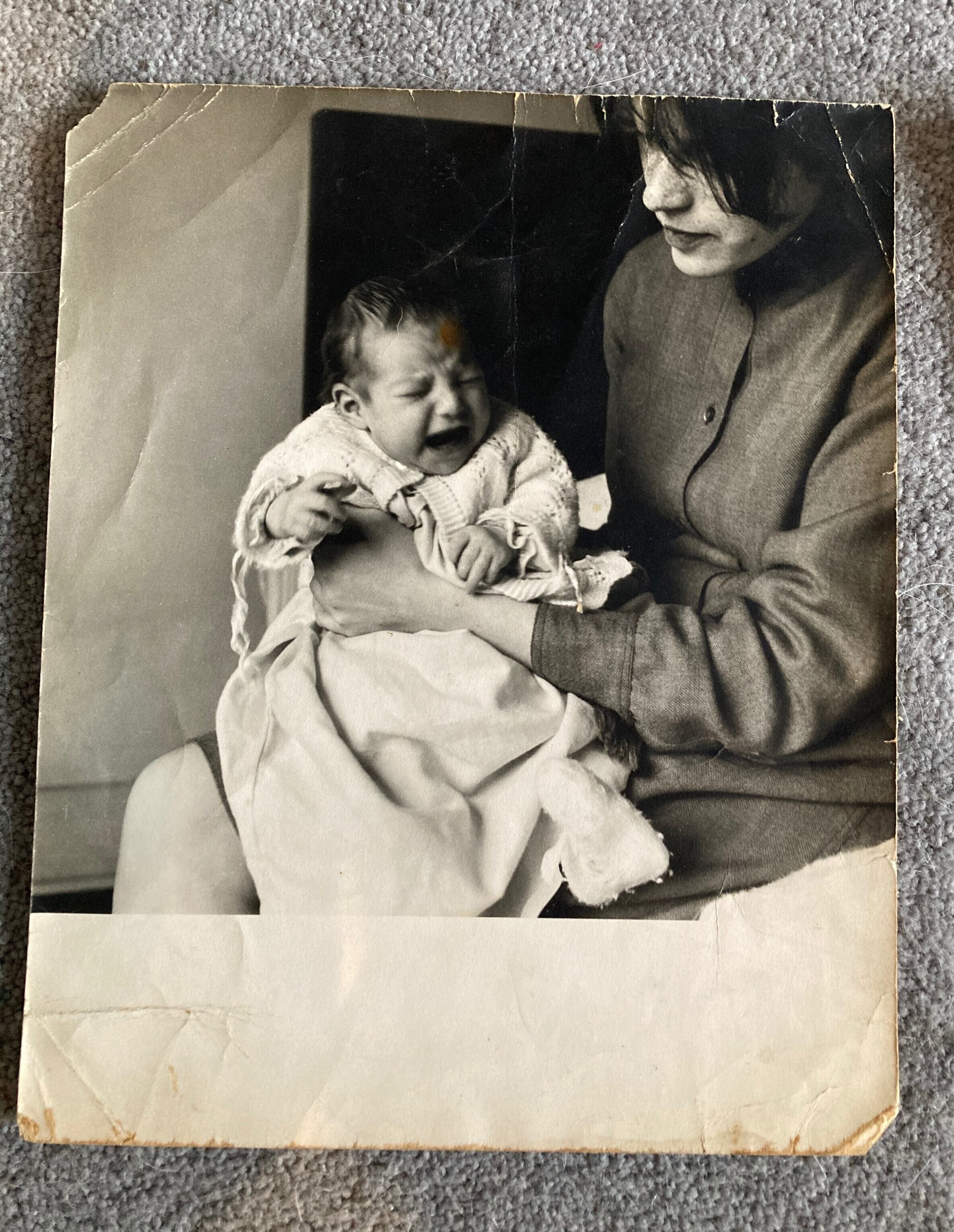

On Being Photographed by John Deakin

By Esther Freud

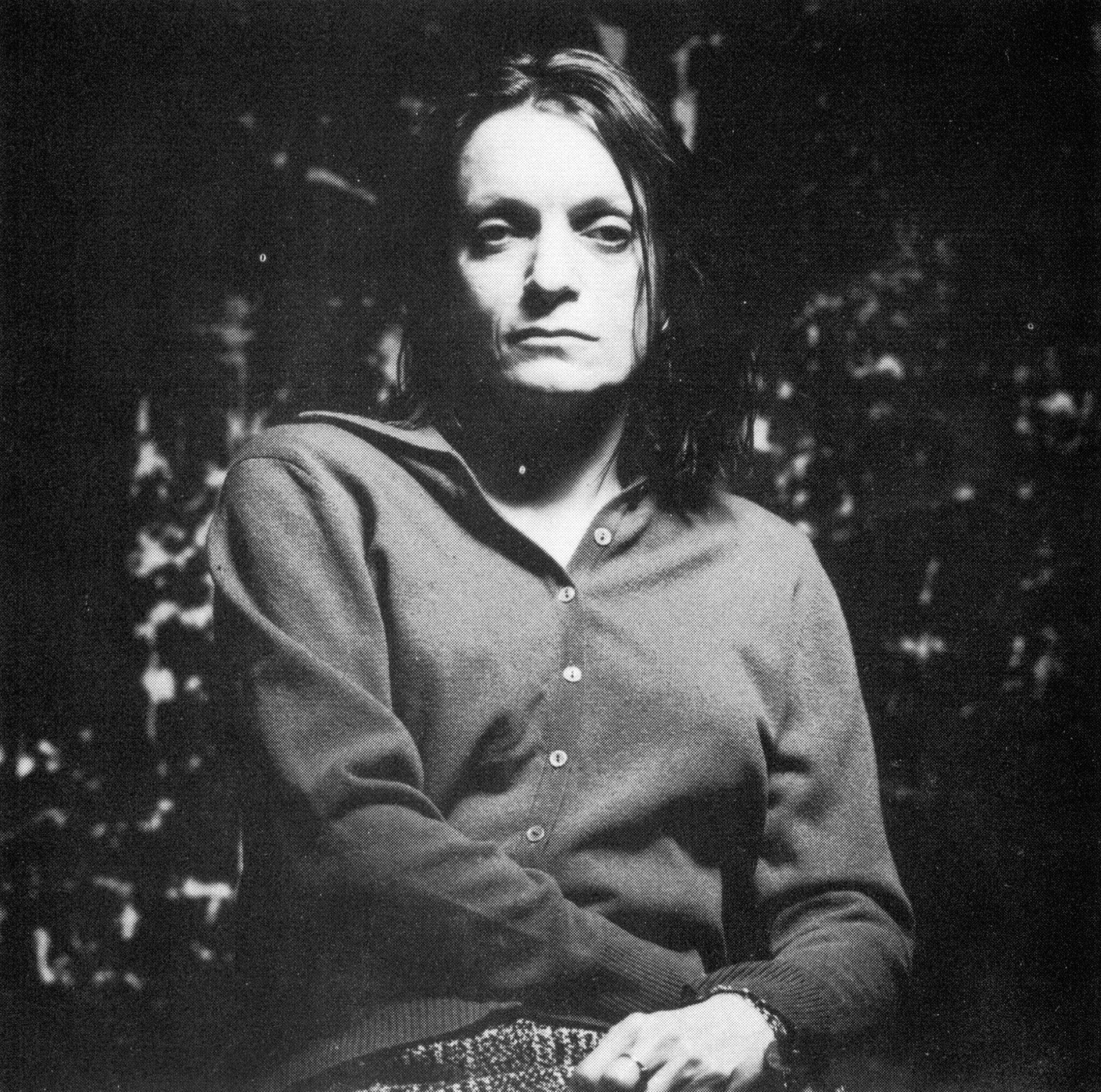

Photographs of Esther Freud with her mother, Bernardine Coverley, taken by John Deakin

While searching for an image for the cover of her latest novel, I COULDN'T LOVE YOU MORE, writer Esther Freud remembered a collection of baby photographs of herself with her mother, Bernardine Coverley, taken by John Deakin, the great photographer of 1950s and 1960s Soho and friend of her father, Lucian Freud. Here, Freud describes rediscovering the photographs and reflects on her mother's individuality, courage and strength as a young woman in the sixties.

I was searching online for an image that might work for the cover of my new book when I came across a photo by John Deakin. It was of a woman, the polka dot shoulder of her dress just visible, her hair, her makeup, her wistful expression - pure sixties.

My novel – I COULDN’T LOVE YOU MORE – is in part a sixties story. It was inspired by my teenage mother who came of age in the bars and coffee shops of Soho, where she met and fell in love with my father, Lucian Freud. Lucian was a friend of Deakin’s. I knew this because he’d been sent to take pictures of me as a baby. Where were they? I wondered. Abandoning the image of the unknown woman (she had, I discovered, been used for the cover of another book) I began searching through old photographs until I found, in their original wax paper sleeve, three creased and tattered prints.

I looked at them now as if for the first time. My mother, her face freckled and impassive, her smart clothes and lipstick failing to detract from the air of bleakness. They told a story, usually disguised. ‘Being fatally drawn to the human race, what I want to do when I take a photograph is make a revelation about it.’ Deakin once said. ‘So my sitters turn into my victims.’ It may be why I’d never really looked at them before, the only baby photographs I had.

Now that I was looking, I saw they’d almost certainly been taken at my father’s studio where he lived, and not as I’d imagined at the flat in Camden where my mother felt herself to have been banished. There were the familiar rumpled bed sheets and the crochet blanket, and me - my mother’s second child, although she was still only twenty - with the clenched fists and direct gaze of a father whose interest by then, she’d told me, lay elsewhere. The colours are muted, sepia tints, an emphasis on shadow, a large black rectangle behind both our heads, and in one, the beveled edge of a mirror reflected in the dark mass of her hair.

My mother came from an Irish/English family recently moved from London to Cork. She’d stayed, entranced by the freedoms of the post war generation of artists and poets, knowing, if she knew anything, that what she wanted was a different life from her parents. Heavily influenced by the doctrines of the Church – her mother was Catholic - and the privations of rationing, her parents were fearful for their eldest daughter, and in turn, she was afraid of them. Too terrified, certainly, to tell them when she became pregnant, certain she’d end up in a home. That her baby would be seized. So she didn’t tell them. Not the first time, or the second. And it wasn’t until several years later when a relative saw her with two small girls waiting at a bus stop and wrote to Ireland: ‘I didn’t know your daughter was married?’ that her secret was revealed.

‘Being fatally drawn to the human race, what I want to do when I take a photograph is make a revelation about it.’ Deakin once said. ‘So my sitters turn into my victims.’

‘You’ve made your bed.’ Came her father’s response. ‘Now you must lie in it.’ But by then, the girl in these photos had grown into a young woman. She had moved away from the sphere of Soho’s bohemia – so dangerous for the vulnerable – and was forging her own life. She’d cast off her passivity, let down her hair, and was making plans to embark on a new adventure – not only providing me with material for my first novel – HIDEOUS KINKY – but on a search for freedom and spiritual enlightenment.

None of the John Deakin images, it transpired, were right for the cover of my novel, which follows a different story to the one my mother embarked on. As I researched my character’s journey from the glamour of an affair with an older man, to a mother and baby home on the outskirts of Cork, forced to work long hours, cleaning and toiling, for the privilege of being ‘looked after’ by the nuns, I was sickened by the cruelty inflicted on so many thousands of women. When I look at my mother, captured here, at what must have been one of her very lowest times, I see the courage, and the strength it took to keep those secrets, and forge ahead with her own, most individual life.

Esther Freud’s latest novel, I COULDN'T LOVE YOU MORE, an unforgettable story of mothers and daughters, wives and muses, secrets and outright lies, is published by Bloomsbury today. Get your copy here.

Freud has written nine novels and one play. After publishing her second novel, PEERLESS FLATS, she was chosen as one of GRANTA's Best Young British novelists, and in 2019 she was made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

May 2021

Interview with DBC Pierre

DBC Pierre © Tobias Wenzel & Darren Biabowe Barnes

DBC Pierre is one of our most uncompromising and original literary voices. His most recent novel, MEANWHILE IN DOPAMINE CITY, published by Faber, was shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize 2020. For CHEERIO, Pierre presents LITTLE SNAKE, a meditation on the ever constant allure of risk, fortune and fate which examines the nature of gambling and the mindset of an obsessive practitioner. To celebrate the paperback publication of MEANWHILE IN DOPAMINE CITY, CHEERIO’s Darren Biabowe Barnes spoke to Pierre about both books, dystopian cities and the similarities between risk and art.

DBB: Pierre, firstly huge, huge congratulations on the paperback publication of MEANWHILE IN DOPAMINE CITY! The novel is real treat, truly original in so many ways. What was the genesis for the book? Was there a specific moment or incident that made you want to write it?

DBCP: This book was a hijacking, I had started out with a mysterious character leaving an underground nightspot, and before that character had even developed, within the first chapter, the digital age had hijacked the whole book. In a way the perfect allegory, as the work went on to describe the utter hijacking of humanity for profit by utopianists who still believe Boolean logic can direct human life.

MEANWHILE IN DOPAMINE CITY satirises both what the digital revolution promised at its inception as well as what we as users have done with the technology since. The world the protagonist Lon lives in, full of surveillance and automation, is dystopian while also totally plausible. Did you set out to write a dystopian novel? And do you see the Londons, New Yorks, Tokyos of tomorrow as dopamine cities?

The Londons, New Yorks and Tokyos of today are already there: so it’s a topian novel, and actually very lenient. Remember not so long ago Facebook reportedly boasted to clients that it could identify and target teens who were feeling down; and not so long ago the Google street-map car was reported to be scraping all the data of the houses it passed; and not so long ago even children’s toys were being sold with listening devices for behavioural data-gathering. The dystopia is here and live: its most dystopian feature is that, like zombies, we don’t give a shit.

One of the most striking things about the book is the way it is presented on the page with two columns of text, mirroring the splintered, schizophrenic way the digital world often works. Why did you decide to tell the story like that?

The old maxim ‘show, don’t tell.’ I had more or less finished the book before deciding it just wasn’t delivering a real sense of how the characters’ lives were unravelling. The glaring flaw of the digital and its relationship with human life is that it’s all still based on a binary system – but what happens is that we’re growing simplified in order to fit the digital world, rather than it attempting to match our sophistication. Also that section of the book was some fun, I just had to find a way to express the binary nature of life all of a sudden, where we’re focussed on two things at once (real life and virtual life), trying to tie them together. But I note, for anyone who thinks it sounds like hard work: you don’t have to read both columns, the story pays off regardless – it just makes us aware that something else in going on in the background.

You won the Booker Prize in 2003 for your debut VERNON GOD LITTLE, which captured hilariously the media cynicism and hysteria of Bush’s presidency. DOPAMINE CITY however lampoons where it is it seems we’re all heading. What is it that draws you to the seedy underbelly of modern life in your writing?

You know, damn, I’d still love to write a historical novel or a fantasy or something, but every day when I wake up I just find that the most lurid, whimsical and tragic environment of all history is the one we have around us. Nothing else is as fascinating to me as why we are this way. And looking back at old drawings and stuff from childhood, they were the same. So it’s a calling, I guess. Anyway historical novels have already been well done.

Your forthcoming meditation on the world of gambling, LITTLE SNAKE, continues that interest via a road-trip through Trinidad and Tobago. Francis Bacon's love of gambling is well known, though I'm not sure he ever made it to Port-au-Spain. Can you tell us a bit more about the book?

LITTLE SNAKE is an enquiry into outrageous fortune. Its starting point was a gamble I took after finding an actual little snake on my doorstep one day, but the book goes on to swivel and dissect what we think (and what science tells us) about probability and its relation to life. There are some gambling anecdotes but I’m more interested in the improbable coincidences of our lives, and the book goes on to propose that we don’t think correctly about the laws of probability. I’m interested in the creation of magic, and as soon as we put all the laws and rules aside which we believe govern our chances in everything, I believe we can find it in our hands.

I also recently read your introduction to Canongate's edition of NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND by Dostoevsky, himself also a huge, huge gambler. What do you think it is about risk and art that make them great bedfellows?

These are precisely the questions that LITTLE SNAKE sets out to examine. Lying behind both art and gambling is a desire, I believe, to wager or waylay our meeting with death: to touch it, ask its truth, seek its favour… Damaged people, and people in the throes of great paradoxes, all set up camp nearer death, and some who survive can do so through art or gambling. The dark jungle of mathematics where the odds of our existences and our deaths reside unseen from us is a magnet for some people. I believe a truth resides there, and some are drawn to play and learn what it is. The last century has given the power of gods to science, and that’s fine – but while science can tell us all the chemicals we need for life to ignite from nothing, it still can’t say how that happens. So there’s a sense that we’re truly on our own when it comes to the big questions of life: and excursions like gambling and art may be some kind of pilgrimage.

Lastly, the cover of DOPAMINE CITY is an absolute work of art. Did you help design it?

Isn’t it cool? It’s the first book for which I didn’t design a cover (not that any were previously used, I would design them for myself). This one, which is a fragment of stylised fennec fox, is the work of Jonathan Pelham for Faber & Faber, as briefed by publisher Alex Bowler. Big shout out to those maestros.

April 2021

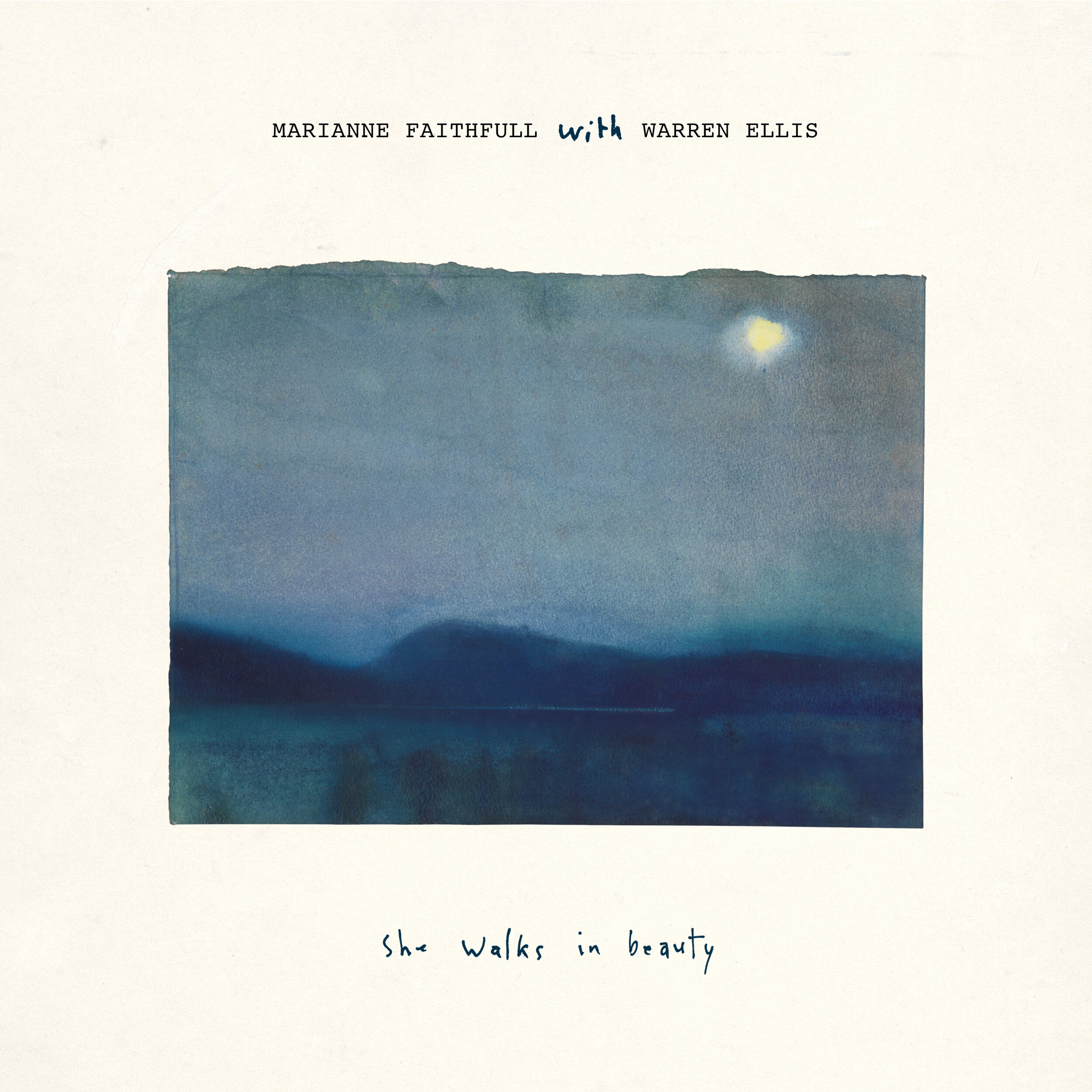

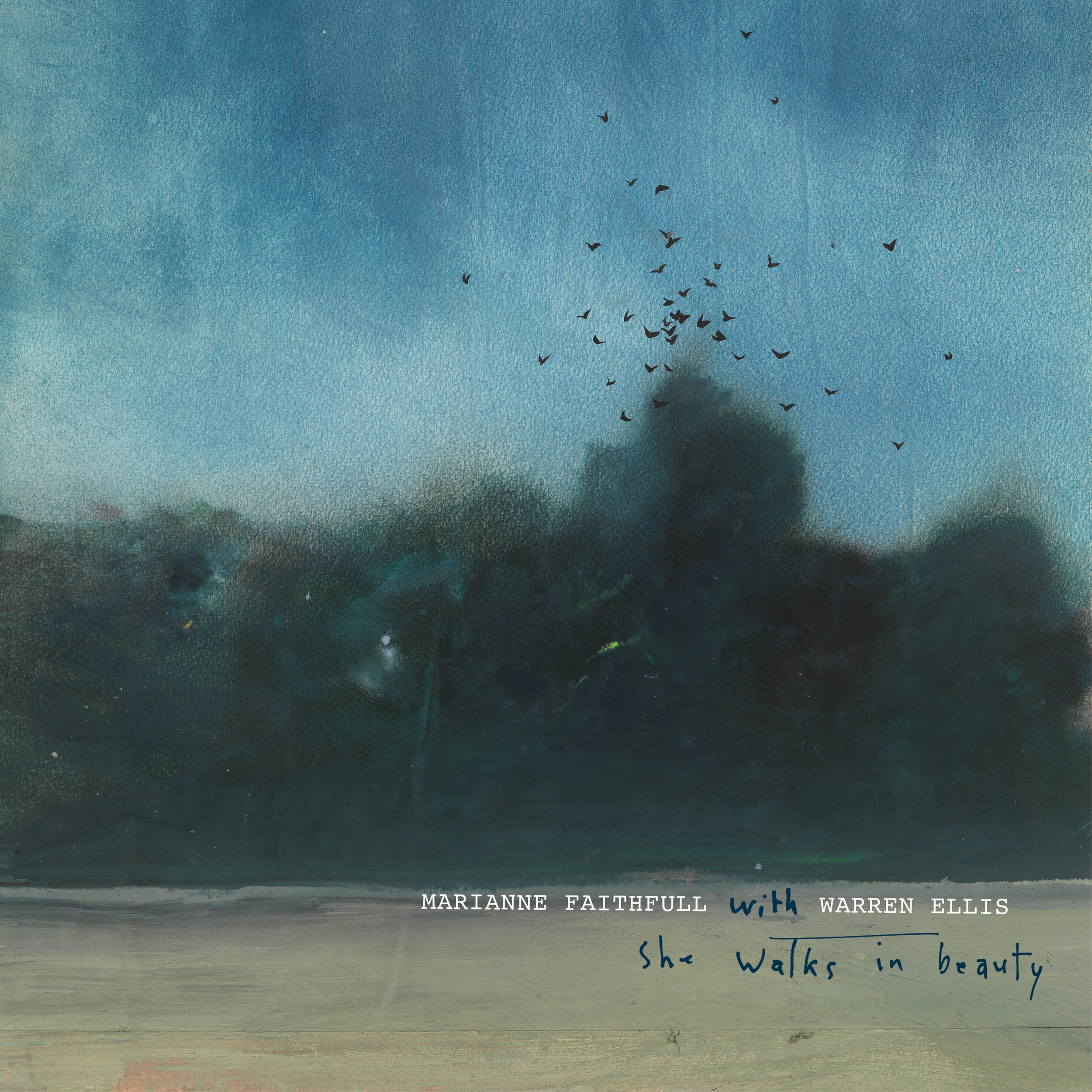

Interview with Marianne Faithfull

Marianne Faithfull and Warren Ellis by Rosie Matheson

We sat down with legendary singer Marianne Faithfull, to discuss her latest album, SHE WALKS IN BEAUTY, which comes out today. Produced with composer Warren Ellis, this highly singular, distinctive album draws on Marianne’s passion for the poetry of Shelley, Keats, Byron, Wordsworth, Tennyson and Thomas Hood - one she’s harboured since girlhood - and features extra special appearances by Nick Cave, Brian Eno and Vincent Ségal.

MF: 1964, I was studying nineteenth century English poets for my A levels with Mrs Simpson – my wonderful English teacher, whom I will never forget. She was inspirational, introducing us all to Byron, Shelley and Keats. I was so happy at that time, learning about these great poets – but then – alas! I was discovered. This interrupted a very happy time – but it’s hard for people to understand that. So, ever since then – I’ve had a bee in my bonnet about it all. I’ve told myself – ok, if you have to make records – why not make a record that celebrates that time in my life? And so, I have.

It’s not to say that it was all bad after that – I am very grateful to everything I’ve learned from Mick and Keith, John and Paul – all those funny people. But I am especially happy to have made this record.

Ronnie Wood, Marianne Faithfull and Keith Richards, Windmill Recording Studio, Dublin, c1992 by Julian Lloyd

SHE WALKS IN BEAUTY Cover Art by Colin Self

I chose Colin Self to create the album cover, partly because his work is beautiful and partly because I love him. He’s been a friend for years, long before he was well known. Now he’s a renowned artist, with paintings and exhibitions at the Tate Gallery and the respect of his fellow artists but I feel the same about him now as I did at the start of knowing him. I like him – I like his wife Jess – I like them.

He and Jess told me that they had a great time picking out the watercolours for the record cover and the video that goes together with the title track She Walks in Beauty. Their choices were authentic. They got it.

And Colin’s work is mysterious, just as aspects of poetry are mysterious. There it is – we can clearly appreciate what we see, what we read or what we hear - but is there another, an extra dimension, behind it? I couldn’t have thought about this sort of thing twenty or thirty years ago.

Colin’s whole attitude is brilliant. He’s honourable, straightforward – a decent man. And there aren’t many of them. There are a few, I suppose.

And of course, the artist is often separate from the person. It’s not always the same. This can apply to musicians, authors, painters and poets. However, someone like Francis (Bacon) – who had his act together from the start of his career – didn’t need to create a persona. He was authentic from the start, long before he was famous and long afterwards. That’s the same with Colin. He hasn’t changed. Success doesn’t mean anything to him. He is and always has been his own man.

SHE WALKS IN BEAUTY Cover Art by Colin Self

I won’t be strong enough to go on tour again – because of long covid, my lungs aren’t strong enough. But other opportunities arrive. Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, who helped so much with SHE WALKS IN BEAUTY, have made a new record – CARNAGE. It’s a masterpiece. They are making a film to go along with CARNAGE – and they have asked me to come along and read something for that film. I will be reading aloud the lyrics of The Galleon Ship – a haunting song from GHOSTEEN, their last record.

I look forward to that.

Marianne Faithfull, Shell Cottage, Carton, Co Kildare, 1993 by Julian Lloyd

Marianne’s album, SHE WALKS IN BEAUTY, and single of the title track is out now.

If you would like to see more of Julian Lloyd's haunting photographs, please go to his online zine, where you can see a selection of his photographic sketches: https://julianrllloyd.myportfolio.com/sketches-zine

Marianne Faithfull by Rosie Matheson

March 2021

Interview with Greta Bellamacina

Greta Bellamacina - who has been commissioned by CHEERIO, along with her husband, the artist Robert Montgomery, to make a film about legendary beat poet Michael Horovitz - is a woman of many talents; poet, actress and filmmaker are all strings to her bow. To celebrate the release of her latest film, HURT BY PARADISE, which she both stars in and directed, we spoke to Greta about the film, poetry and finding magic in the mundane.

Poetry is at the core of your film, HURT BY PARADISE. What draws you to poetry as an art form?

I like the profound and hard nature of poetry. Poetry is for the suffered and the suffering, the broken and the unanswered. I find it one of the most freeing languages to speak in. I am yet to find another art form that cuts straight in with no return.

The written word is a theme in the film – characters write poetry, conduct online relationships via text, receive rejection letters. How did you start writing?

Like many things I started instinctively. I’ve always felt a profound need to write things down. Writing almost feels like a religion. You quietly bare your soul, again and again. You sit in solitude with your thoughts and your fingers. Words have always felt like quiet prayers. There is something renewing about putting down words like bricks, like a song, like a halo. I don’t know why, but it feels like the truest form of love.

The film itself is constructed like a poem; scenes are punctuated by slides with ‘Verse One…’, ‘Verse Two…’ written on them, and lines of recited poetry are layered over shots. What was the intention behind that?

I wanted the characters to feel incomplete and multifaceted, like a poem, like life. These things are complicated and unexplained and searching. I wanted the characters to feel as lifelike as possible. I didn’t want the main resolve to be the plot but instead I wanted it to be something small, a small awakening in the characters instead.

How does poetry influence your filmmaking?

In film you want to create a world within a world. You want to find the magic within the mundane, just like with poetry you want to find the sacred in the everyday. To quote Arab Strap, “a wallflower in the darkness”.

Music seems to play an important role in the film. How does music inspire you? Does it inspire your poetry?

We used a lot of our friends bands music in the film, the soundtrack is very much a homage to the voices of our surroundings. The live music of Bruno Wizard and the voices of the band Ambulances.

I wanted the soundtrack to feel like you were wandering the empty streets of Camden or on the night bus home with your iPod. I wanted to try and capture that melancholic state of mind.

The film often feels like a love letter to London, with beautiful sequences of shots of the city interspersed through the film. How much does place inspire you creatively?

I am like a moth. I like to follow the light around the house. I find it hard to work when the sun is out. I like to be close to the light in some way. I also need a certain amount of space from my work in order to finish it. I often work on a few projects at one time, I find this helps give a perspective. Especially when editing, there needs to be enough oxygen to bring it back to life. Most of the time my best thoughts are in the morning or the evening, life seems to get in the way in the middle.

I know that you’ve recently moved to the countryside. Does the poetry you write change when you’re in the country? If so, how?

The sky is much more open here. The days feel longer and my thoughts seem to grow more. The countryside and the cities have their own clockwork. I feel deeper in the weather here. I think my poetry becomes closer to it too. Life fizzes in a different way. The world feel more high res and awake. It is hard to miss it. Nature is a great healer, I feel very lucky to be closer to it.

What inspires your poetry?

A lot of things. It can be a stranger, a road sign, a fallen down building, something on the news. I like finding the unexpected.

How has the lockdown affected your work & process?

Lockdown felt very reflective. Like someone has been holding up a giant mirror and we were all forced to look inside of it for a very longtime. I am not sure how lockdown affected my process but it definitely forced me to slow down. I started writing a new collection called Biography Of The Wind. It is sort of a diary of the wind hitting objects, a world before the cars and the make believe and consciousness.

"Writing almost feels like a religion. You quietly bare your soul, again and again"

Has becoming a mother affected your poetry and your relationship to writing? If so, how?

I’ve felt a new closeness to my lineage as a woman and my voice. I think this has filtered into my work, not just as a writer but as a performer also. I feel more compelled to tell stories of complicated women. Motherhood is one facet to being female, I think it’s important for it not to be the only defining one.

Do you have a trick for getting into a creative headspace, or do you just write when inspiration strikes?

I try to keep a daily routine, I think this is useful to keep a pace and momentum going. Sometimes you don't feel creative but it is important to give yourself a quiet space to think and digest and explore.

What tips would you give to aspiring poets?

Give your whole heart.

March 2021

Interview with Kandace Siobhan Walker, winner of The White Review Poet’s Prize 2020

Kandace Siobhan Walker

When did you start writing poetry, and what made you begin?

I started writing poetry as a teenager. I wanted to be a musician, and I started out by writing lyrics in the style of my favourite pop punk bands and reading writers that they mentioned in interviews. But at school poetry was so boring, the poems we were taught and the way we were trained to analyse them seemed so far removed from reality. I didn’t really know anything about contemporary poetry and the craft of poem-making until I went to university.

The judges of the White Review Poet’s Prize praised the ‘restless energy’ in your poems, and I felt there was an almost musical, jazz-like undercurrent in many of them. How intentional is that, and what inspires it?

I feel like there’s a misconception about jazz that it’s always improvised on the spot, like they walk in the studio and just play. But what that requires is a lot of rehearsal, becoming familiar with different concepts, so that you can play with ideas and come out with something that feels simultaneously obvious and startling. It’s the same with poetry – you have to know the rules to play. When I’m writing I riff on sounds and rhymes and phrases until I surprise myself. My favourite poems are the ones that make me double-take, like a funny anecdote at a party, so I guess it’s intentional, I do like my poems to have that quality. A bit chaotic, a bit comedic, like a conspiracy theorist gesticulating wildly at their map of red string.

They also described your approach to poem-making as being ‘as improvisationally deft as it is technically assured’. How important is it to you that your poems contain a feeling of improvisation?

It’s funny, and flattering, to hear my work described as improvisational, because I spend so many hours moving commas around that when I arrive at a final draft it feels very measured to me. I do like aha! moments in my poems, in the language I use. Every word has its natural or logical associations, and I have fun subverting expectations of what idea or image will come next. It’s testing the limits of my own imagination, like can I make this make sense?

What draws you to poetry as an art form?

With poetry, I can be clear and inconclusive at the same time. It’s more gestures than arguments. I can feel my way around a thought without feeling like I need to come up with an answer. It makes some ideas that are easier to explore.

I know that you write short stories as well as poems. What do you view as the main differences between the two forms?

The way I write short stories, I feel like I am trying to prove a hypothesis. It’s an additive style: regardless of the story’s structure, there’s a linearity of events and ideas that is fairly essayistic. I feel like poetry moves in the opposite direction.

How or why do you choose to express something – a thought, a feeling, an idea - as a poem rather than a story, or vice versa?

It’s usually a process of elimination. I might try an idea as a short story, and in the process of trying to plot it or write it out, I’ll find myself getting frustrated and try it as a poem or an essay. It’s easier for me to tell when a poem needs to be a short story, because the narrative voice just won’t let go.

Image c/o The White Review

How does place inspire how and what you write?

Place is in everything. The feeling of being in a specific place, the sounds and emotions and the way the air smells, the people you encounter walking down the street. I’m interested in how the world makes us and is made by us, and it’s hard to write about that without understanding geography – people and their environments. The better I understand the social rules and relations that define the place I’m in, the easier it is for me to write.

How has the lockdown affected your process and work?

During the first lockdown I was furloughed and living the writer in the woods life, so it was really generative for me. I’m autistic so not having to mask everyday at work meant I had a lot more energy to do anything else. But winter lockdown was not fun! I had to be more intentional about routine and basic self-care, which is so boring but I’ve found the best way for me to be able to write is to get a good night’s sleep, so now I have a bedtime.

What space do you think there is for poetry today?

I think there’s a necessary space for poetry as a tool in the global movement for liberation, and for me the most important contemporary work is that which reaffirms the necessity of our collective liberation. And I feel a deep gratitude to the people who continue to push at the boundaries of the form and the industry to make space for and within poetry.

What tips would you give to aspiring poets?

Read loads. Do some covers. And take your work seriously, or you won’t have any fun.

Read ‘Prism’ from Walker’s winning portfolio here.

Walker receives a prize of £2,500, and her portfolio will be published in a forthcoming issue of THE WHITE REVIEW. This year, the prize was run in partnership with CHEERIO Publishing, a partnership that will run for a minimum of three years.

Image c/o The White Review

February 2021

Becoming Isabel Rawsthorne

by Anne Lambton

Anne Lambton as Isabel Rawsthorne in John Maybury’s 1998 film

LOVE IS THE DEVIL: STUDY FOR A PORTRAIT OF FRANCIS BACON.

Photo by British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)©1998

In 1997, John Maybury asked me to play Isabel Rawsthorne in the film he was soon to direct about Francis Bacon – LOVE IS THE DEVIL. Back then, information about female artists was harder to find. All I knew about Isabel at the time was that she was adored by great artists and she adored sex. A good start, but I needed more.

I soon learned that she’d left the safety of her home in Liverpool at the age of 19 to immerse herself in the art world. Very early on she realised that money was a necessity for creative independence. She engineered a meeting with Jacob Epstein and offered herself to him as a model. A deal was struck and, with the money she earned, her life effectively began. She and Epstein painted together and they grew very close – according to most, they were lovers.

She was soon accepted as a collaborator – and, as with Epstein, oftentimes a lover - of many of the greatest artists of the twentieth century. Her circle included such writers as Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre and Ian Fleming, as well as Alberto Giacommetti, Pablo Picasso and Francis Bacon. She also formed and maintained close friendships with many composers and musicians, including Constant Lambert and Alan Rawsthorne, both of whom she later married.

Isabel Rawsthorne, Three Fish, 1948

© Warwick Llewellyn Nicholas Estate.

All rights reserved, DACS 2020

Though she was both a friend and a muse to many of the period’s most influential artists, she was also to become a remarkable artist in her own right.

I began to recognise aspects of her life in my own. I too had left the safety of my home at a young age to immerse myself in the art world – I was even younger than Isabel when I left, aged 17, and my destination was N.Y.C to work in Andy Warhol’s factory. Andy and I became very close. Lovers? Definitely not - but with the money I earned, like Isabel with Epstein, my life began. Being immersed in such a creative milieu helped me to pluck up the nerve to become an actress, an ambition of mine since the age of six.

Yet it was the smaller details shared with me by the wonderful director/designer Philip Prowse that really gave me a sense of Isabel’s character.

“She had the weight of a man.” He told me.

“But not masculine?” I queried.

“No, not masculine at all,” he confirmed - “rather grand.”

In the early sixties, Isabel and Philip were both working on Ballets for Covent Garden - Isabel with choreographer Alfred Rodrigues on JABEZ AND THE DEVIL, and Philip with Kenneth MacMillan, on an abstract piece called DIVERSIONS. Philip would run into Isabel in corridors and the green room, but mainly in The Nag’s Head. Whenever they met, she always had on her Harris tweeds, matching coat and skirt, court shoes and perfectly painted scarlet lips. That is, apart from on the inside of her mouth, where the constant wine glass friction had worn the lipstick away completely. More than all the paintings, photographs, observations by or about her, this somehow did it for me. The make-up team on the film got it perfectly - and the face of Isabel ‘appeared’.

From the very first day of shooting, John was ingenious. Being forbidden by Bacon’s gallery to reproduce his artworks, he made the film itself into a Francis Bacon painting, shooting distorted images through wine glasses, warped mirrors and chunky glass ashtrays, especially in the scenes shot in the original Colony room, which was run at the time by Michael Wojas.

As the film crew set up, Michael was almost overcome by this moving tableau, a smattering of the most important part of his life. Here was gutter glamour revived, once again drinking, bitching and misbehaving; chaotic, crowded, many of us tripping over cables and dodging cameras in the confined space of the famously seedy drinking club. A few of the original members wandered in, took the drinks Michael knew they wanted, and settled into their habitual seats, supping steadily, quietly, watching their past lives weave by as we filmed. One of them stopped me, “You must be Isabel?” I raised my glass in affirmation and a toast was given – “Ah, Mrs. Rawsthorne – welcome back darling!” .

Francis Bacon, Study of Isabel Rawsthorne, 1970

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2020.

Isabel Rawsthorne (1912-1992) was hidden in plain sight. From celebrated portraits of her in Berlin to sketches in the Tate, likenesses in museums around the world have kept her secrets. This book combs the depths of her fascinating life and the extraordinary art she herself made from it. Carol Jacobi re-examines the pre- and post-war art history of which Rawsthorne was a part, tracing the painter’s life and art through the upheavals of the 20th century and her intense and often unconventional relationships with some of its most revered figures.

The first in the Studies in Art series from The Estate of Francis Bacon Publishing, overseen by series editor Martin Harrison, this richly-illustrated book takes the lead from Rawsthorne’s compelling biography to reconsider sixty years of her art, now housed in several major public collections.